Why a Ticketing Tweak Is Actually a Real Estate Story

From January 1, 2026, Riyadh Metro is no longer just a pay per ride system; for a big slice of the population it becomes a subscription. Standard class annual passes are set at around SAR 1,260, first class at about SAR 3,150, with deeply discounted semester passes for students (≈SAR 260 per term).

That sounds like a simple fare update. It isn’t. In a city where the metro has already:

- Reached 176 km of fully driverless track across six lines and 85 stations,

- Been recognised by Guinness as the world’s longest driverless metro network,

- Carried more than 100 million passengers in its first nine months of full operation,

locking in “all you can ride” pricing changes the economics of where people live, shop, and build. The moment you cap a commuter’s annual transport bill, you change the value of being near a station. That is the essence of transit oriented development (TOD) and land value capture: infrastructure alters relative accessibility, and accessibility gets capitalised into rents, yields, and land prices.

For Saudi and regional investors, the new passes arrive on top of two other forces:

- A visible “metro premium” in Riyadh residential prices around the new stations, already quantified in recent Knight Frank work.

- A policy push to rebalance affordability in Riyadh (five year rent freeze, white land enforcement) while still backing major urban megaprojects and TOD nodes such as King Salman Park, Diriyah Gate, New Murabba and Qiddiya.

This article unpacks how the 2026 pass regime is likely to interact with that backdrop and what it means for rents, footfall patterns and TOD anchored strategies over the next five years.

Global Landscape: How Cheap, Predictable Transit Gets Capitalised into Land

Internationally, the link between high quality urban rail and property values is no longer a hypothesis; it’s an empirical baseline. Recent work on light rail and metro systems shows:

- New or expanded rail lines typically lift nearby property values by mid single to low double digits versus control areas, with effects strongest within 500 meters of stations and where bus or feeder networks are dense.

- The impact is not instantaneous; it tends to build as networks bed in, frequency improves, and commuters internalise time and cost savings.

Transit passes matter because they flatten the marginal cost of an additional trip to nearly zero for frequent riders. Once your annual spend is sunk, each extra stop testing a new café, renting a co-working desk by a station, visiting a mall on a different line feels “free.” In value capture terms, that accelerates the monetisation of location advantages:

- High frequency, multi purpose travel becomes normal rather than exceptional.

- Retail and F&B near stations see more footfall from non commute trips.

- Higher density near stations becomes more viable because the transit system absorbs the mobility load.

Global land value capture (LVC) practice has been built around this logic. Contemporary frameworks, from ADB’s TOD work in Asia to recent regional value capture studies in North America, model how incremental tax or fee instruments can be layered on top of uplift created by rail investments to fund the infrastructure itself.

Saudi Arabia does not yet run a mature property tax regime, but the same dynamics: uplift, clustering, and higher residual land values show up in transaction data, land assembly pricing and required yields.

Regional (MENA) Context: Metro Networks and Real Estate Uplift

Across MENA, two storylines are relevant for Riyadh:

- Metro proximity as a pricing signal.

Analysis of Dubai’s metro impact shows neighbourhoods within a 10–15 minute walk of stations structurally outperforming the wider market on both rents and sale prices. - Integrated bus metro systems as TOD enablers.

Cairo, Riyadh, and Gulf cities are converging on a model where metro, bus, and increasingly e bus networks are integrated, with unified ticketing and platform level upgrades to station areas.

The lesson is straightforward: once a metro reaches city scale and integrates with buses, real estate starts to price locations not just by car access or arterial road visibility, but by station catchment and frequency. Annual passes accelerate that shift.

Riyadh’s Starting Point: A Metro That Is Already Moving Prices

Network scale and ridership

Riyadh now operates a 176 km, six line, 85 station driverless network, officially recognised as the world’s longest driverless metro system. The system is fully integrated with a 53 route, 700 bus, 2,900 stop Riyadh Bus network, with unified ticketing and routing delivered through the Darb app.

Within nine months of the main lines opening, the metro had already carried more than 100 million passengers, signalling strong latent demand for non-car mobility. By 2030, some market analysts expect the system to handle around 1.5 million passengers per day as the city densifies along the network.

The emerging “metro premium” in residential markets

The residential impact is already visible before the 2026 pass reform. Knight Frank’s 2025 white paper, The Value of Access: Measuring the Impact of Riyadh Metro on Real Estate, documents:

- Villas in Al Yarmuk near metro stations rising by roughly 78% between 2023 and 2025, compared with about 22% in peripheral areas.

- Homes within walking distance of stations in districts like Tuwaiq and Al Malqa gaining around 20% between mid 2023 and mid 2025 roughly double the rate of less connected locations.

- Nearly 18% of Riyadh’s population now live within a 15 minute walk of a metro station.

These are classic TOD effects: improved accessibility is already being capitalised into housing values, with differentiated trajectories emerging at a neighbourhood level as the network moves from construction to normal operation.

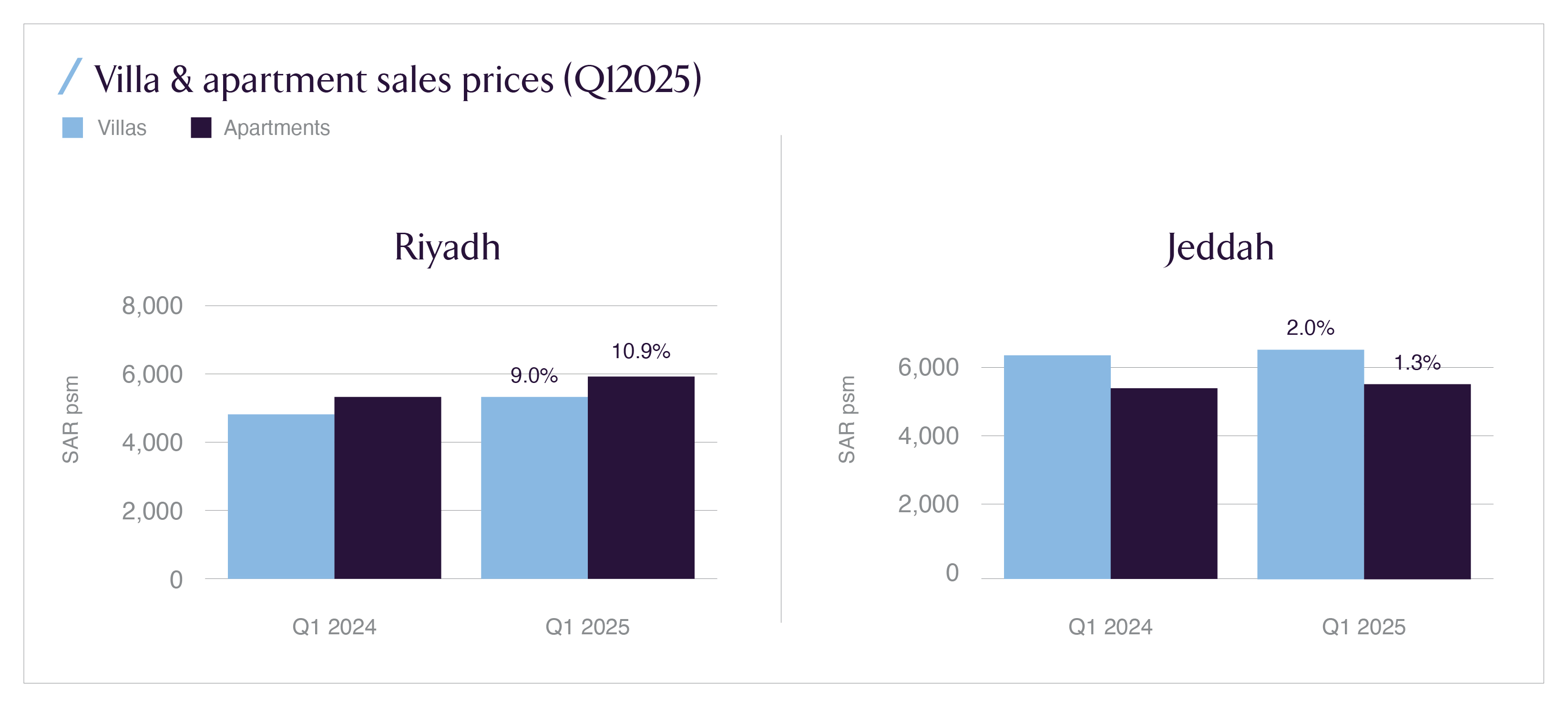

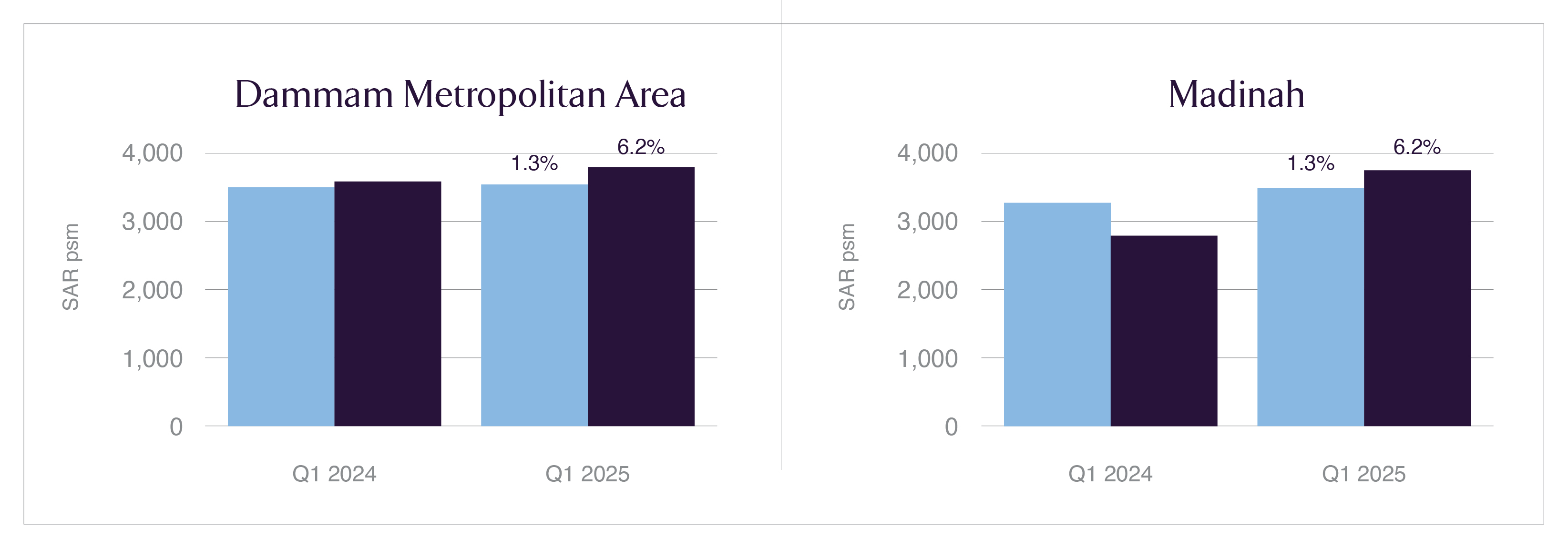

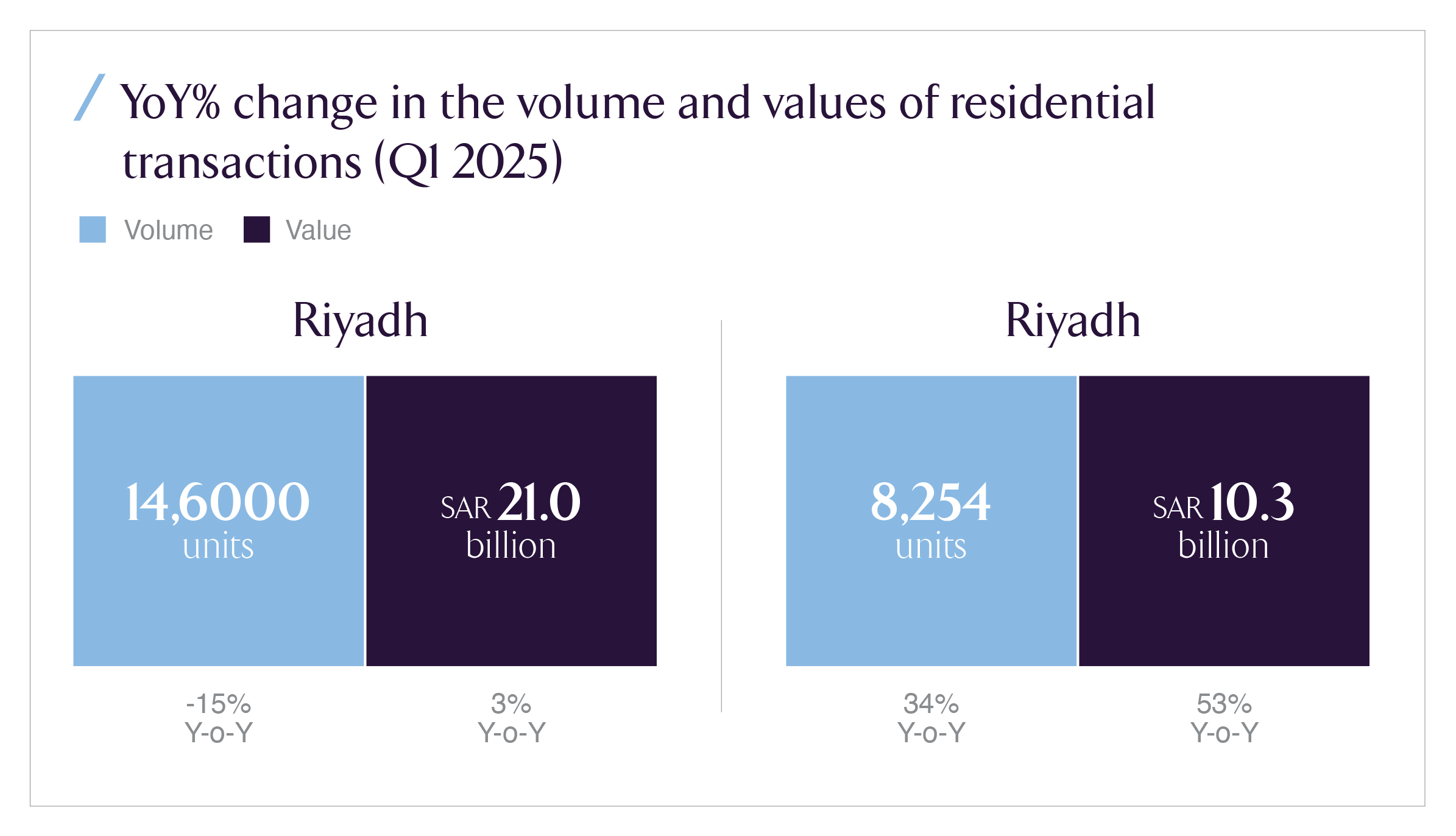

On top of that, Knight Frank’s Saudi Arabia Residential Market Dashboard shows Riyadh leading national residential price growth into 2024–2025, even as affordability constraints and new supply in other cities temper momentum.

What Changes in 2026: From Pay Per Ride to Subscription Economics

As of late 2024 and 2025, Riyadh Metro pricing is built around short duration and monthly passes:

- Standard class: two hour tickets from SAR 4, three day passes at SAR 20, seven day at SAR 40, and 30 days at SAR 140.

- First class: higher tiers, with 2 hour, 3 day, 7 day and 30 day passes priced at about SAR 10, 50, 100 and 350 respectively.

This structure already favours frequent riders, but it still forces most residents to think in monthly or weekly increments. The 2026 regime introduces:

- Annual Pass (standard class): ≈SAR 1,260.

- Annual Pass (first class): ≈SAR 3,150.

- Semester Pass (students): ≈SAR 260 per academic term, with unlimited trips across metro and integrated bus.

For a daily commuter who previously bought 30 day standard passes for 12 months, the annual pass reduces their effective monthly bill from around SAR 140 to about SAR 105, roughly a 25% discount. For a student commuting five days a week across a four month semester, the semester pass compresses what would have been several multiples of that cost into a single, predictable outlay.

The key for property markets is not just the discount, but the predictability and unlimited nature of travel: once you hold a pass, each marginal trip is effectively cost free. That changes location choice, trip chaining (combining errands, jobs, study and leisure in a single circuit), and the value of being within a short walk of a station.

Transmission Channels: How Passes Flow Through to Rents, Footfall, and TOD

Residential rents and capital values near stations

In a rent controlled Riyadh, there is an important distinction between:

- Regulated rent levels on existing leases, which are frozen for five years; and

- Capital values and new build pricing, which remain market driven and already reflect metro related uplift.

Annual passes strengthen the case for:

- Higher premiums on new developments within true walkable catchments (≈500–800 meters of stations), especially if they also offer first /last mile amenities (shuttle, shaded walkways, micro mobility docks).

- Infill and redevelopment in older villa districts near stations, where owners can monetise both existing uplift and future demand from tenants who see metro access as a hedge against fuel, congestion, and parking uncertainty.

The Knight Frank evidence suggests that even before passes, metros were producing a 2–3x differential in price growth between stations adjacent and peripheral areas. Passes intensify that by locking in a structural cost advantage for car light households: a family that replaces a second car with an annual pass is effectively freeing thousands of riyals of annual cash flow, which can either support a higher rent or service a larger mortgage.

For Saudi investors, the relevant questions aren’t “will prices go up?” they already have but:

- Which station adjacent micro markets still misprice the value of unlimited transit?

- Which schemes are combining metro access with credible community amenities (schools, clinics, retail) rather than treating stations as a cosmetic marketing line?

Retail, F&B and footfall dynamics

Value capture is not only about residential.

With annual passes, we should expect:

- More off-peak leisure trips (weekends, evenings) into nodes like KAFD, King Abdullah Financial District stations, King Salman Park, central malls and entertainment districts.

- Higher multi stop trip chaining, where a commuter stops for groceries or coffee at a station adjacent strip because there is no incremental fare cost.

That tends to compress retail risk into the station’s walkable catchment:

- Units physically visible from station exits, or embedded in mixed use projects above/beside stations, should see structurally stronger footfall growth.

- Secondary retail a kilometre away but still marketed as “metro adjacent” may see less of this pass driven uplift unless last mile access is carefully designed.

Combined with Riyadh’s broader consumption and tourism push, this gives station integrated retail a defensible volume edge, which can support:

- Higher base rents,

- Turnover linked leases that capture upside from footfall growth, and

- Development of curated F&B or experience oriented clusters at key interchange stations.

TOD, land assembly, and value capture

From a TOD standpoint, the 2026 pass regime strengthens the logic for:

- Up zoning and higher FAR immediately around stations, allowing developers to monetise the uplift via taller and denser schemes.

- Structured land value capture instruments even in a Saudi context without general property tax, there is room for station area betterment fees, joint development concessions, long lease air rights, and targeted contributions tied to infrastructure improvements (e.g., station plazas, pedestrian bridges).

If you view a station catchment as a mini balance sheet, annual passes increase the “cash flow engine” by encouraging heavier utilisation of the network. The rail asset is sunk; the main marginal costs are energy and O&M. Every additional trip that converts into a higher rent unit, a more productive retail cluster, or better occupied office stock effectively raises the return on that sunk capital even if the fare per trip falls.

Challenges: Constraints and Second Order Risks

The story is not one directional. Investors need to track three specific friction points.

- Rent freeze interaction.

The five year rent freeze in Riyadh caps rent levels on existing leases at their latest rent, aiming to stabilise households after a 30–40% run up in recent years. This may:- Delay the full pass driven rent premium in the secondary market.

- Push more of the uplift into capital values, as buyers pay for future re rating potential once the freeze expires or as leases turn over.

- Equity and displacement risk around stations.

Global experience suggests TOD can displace lower income households to less connected peripheries if there is no deliberate affordable housing and inclusion policy. As metro proximate property in Riyadh continues to re rate, there is a risk that:- Blue collar and lower middle income residents get priced out of the very locations where passes would have helped them most.

- Political and social pressure triggers ad hoc interventions that distort project economics (e.g., abrupt zoning shifts or informal expectations around pricing).

- Execution on TOD urban design.

Cheap passes alone don’t create walkable, valuable station areas. The design fundamentals safe crossings, shade, last mile services, parking management, mixed use zoning will determine whether station catchments function as genuine TOD nodes or remain park and ride islands in a car dominated fabric.

For capital allocators, the challenge is to back projects and platforms that are aligned with the city’s long term TOD direction, not merely adjacent to a station on paper.

Strategic Responses and Solutions for Investors

With those constraints in mind, how can Saudi and regional investors position themselves?

A few practical angles:

- Prioritise true walkable catchments, not just “metro in the brochure.”

Focus on sites where you can measure actual pedestrian connectivity to station exits today or via committed, funded public realm works. Tie underwriting assumptions to Knight Frank’s observed differentials in near station vs peripheral price growth, not to generic city wide averages. - Blend residential with resilient everyday retail.

Annual passes favour everyday use: supermarkets, pharmacies, clinics, cafés and budget F&B located at or near stations. Structuring mixed use projects with a strong essential services layer can stabilise cash flows and reduce cyclicality. - Align with potential value capture instruments.

Even without explicit TOD legislation, investors can structure:- Long leasehold or revenue sharing deals on station adjacent public land.

- Joint development agreements with municipal or royal commission entities, where private capital funds station area enhancements in exchange for enhanced development rights.

- Evidence from recent regional value capture analyses shows that targeted tools like tax increment style mechanisms and special assessments can cover a meaningful share (10–30%+) of transit related capital costs when station area development is dense enough.

- Integrate past economics into underwriting models.

The effective reduction in annual travel costs for pass holders should appear in your affordability and demand assumptions. For example, a car light household’s transport savings can be modelled as an increment to housing budget, justifying slightly higher rents or purchase prices in well connected micro markets. - Lean into student and knowledge worker corridors.

Semester passes target students explicitly. Mapping universities, training institutes and education clusters against current or planned stations can surface micro markets where student housing, co living and mid market apartments close to metro stops may see above trend demand.

Keeping this in narrative prose rather than long bullet lists, the underlying message is simple: the passes are not a marginal perk; they rebalance the household budget line between “transport” and “housing,” and TOD aligned assets sit on the right side of that rebalancing.

Benefits: Scenarios for 2026–2030

If Riyadh executes on the combination of:

- A mature, fully operational metro + bus network,

- Predictable, affordable annual and semester passes, and

- Progressively more structured TOD policies around key nodes,

then three medium term benefits become plausible.

First, a more elastic, transit anchored rental market within policy limits.

The rent freeze will suppress part of the adjustment in headline rents, but transaction and valuation data are likely to show continued outperformance in station catchments. Investors who secure assets in these zones now are effectively buying an option on post freeze re rating, backed by a fixed floor of pass driven demand.

Second, more bankable retail and mixed use projects at interchange and destination hubs.

As annual pass penetration rises and passenger volumes compound towards the 1.5 million per day range, the case for structured, multi level station area retail becomes stronger. That is especially true at interchanges that also serve giga projects or major public spaces.

Third, a clearer blueprint for Saudi TOD and land value capture.

Riyadh is the testbed. If decision makers can demonstrate that metro + passes + TOD zoning plus modest value capture tools can finance public realm upgrades and part of the network’s long term capital needs, the same playbook can travel to Jeddah, Dammam and future regional rail or BRT corridors.

For institutional capital, the upside is not just asset level outperformance; it is alignment with a structural shift in how Saudi cities monetise infrastructure and organise growth.

Recap: What to Watch as Passes Go Live

Riyadh’s 2026 metro pass regime sits at the intersection of transport policy, affordability politics and real estate economics. The core takeaway for a Saudi focused investor is:

- The network is already reshaping residential values and accessibility.

- Annual and semester passes deepen and stabilize usage, changing the economics of station adjacent land and assets.

- Policy constraints (rent freezes, white land taxes, nascent value capture frameworks) will shape how that uplift is distributed between landlords, developers, and the state.

In practice, the next 24–36 months will be about micro market selection and execution:

- Which stations emerge as genuine TOD hubs with walkable, mixed use envelopes?

- How quickly do pass adoption rates climb among students and daily commuters?

- Where do Knight Frank style “metro premiums” accelerate, plateau, or spread into secondary corridors?

If you treat the passes as just another transport story, you will miss the main signal. Treated correctly, they are a pricing instrument that turns Riyadh’s rail network from a large capital project into a more predictable, monetisable foundation for long duration real estate returns.