Saudi Arabia’s new Law of Real Estate Ownership by Non Saudis, published in July 2025 and due to enter into force around January 2026, is not a cosmetic tweak to an already open market. It is a structural regime shift that rewires who can own what, where, and for which purposes including, for the first time, tightly defined pathways into Makkah and Madinah for foreign capital under specific conditions.

For Saudi and international investors, the timing is non-trivial. Global commercial real estate is still digesting the fastest rate cycle in a generation, with transaction volumes in 2023 slumping to their lowest level since 2012 and capital flows re pricing risk across regions and asset classes. In parallel, the Kingdom’s own real estate market is scaling rapidly: total real estate transactions reached about SAR 2.5 trillion in 2024 (≈USD 533 billion), more than 622,000 deals covering 5.8 billion square meters.

The opening to foreign freehold ownership in broader geographies plus controlled access to holy city zones therefore lands at an intersection of global capital looking for defensible yield, and a domestic market where prices and volumes are already being reshaped by Vision 2030, rent freeze directives, White Land Tax enforcement, and large tourism and infrastructure projects.

This article focuses on what the January 2026 regime means in practice: for cross border capital flows, for pricing in gateway and secondary cities, for religious tourism corridors, and for how Saudi investors should think about ticket sizes and structures when foreign buyers become a permanent part of the order book.

Global Backdrop: Cross Border Capital in a Higher for Longer World

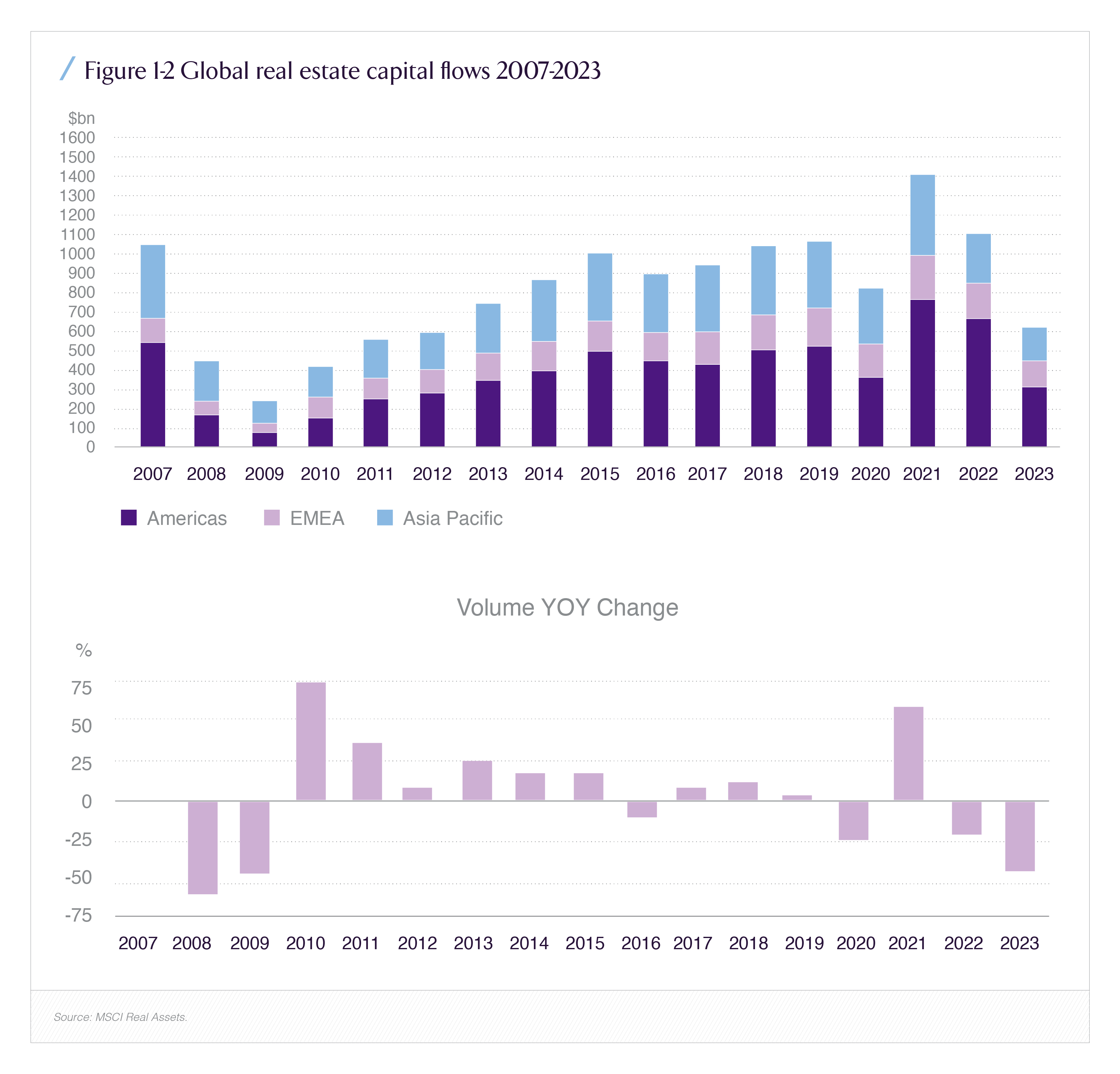

Global commercial real estate is emerging from a sharp contraction in transaction activity. According to the 2024 Global edition of Emerging Trends in Real Estate, MSCI Real Assets data show that transactions involving income producing properties fell 48% in 2023 to about USD 615 billion, the lowest level since 2012. The drop is broad based, reflecting elevated policy rates, re pricing of office risk, tighter bank balance sheets, and geopolitical risk premia.

At the same time, cross border capital has become more selective rather than disappearing. Investors are concentrating exposure into jurisdictions perceived to be macro stable, infrastructure heavy, and policy credible. Within this context, a rules based opening of Saudi freehold markets to non Saudis in a country with an investment grade sovereign balance sheet and large state backed urban mega projects can change how regional allocations are constructed, even if global flows remain subdued in aggregate.

The chart underscores three points relevant to Saudi policy makers and allocators:

- Global volumes are cyclically depressed, so new, investable markets can capture outsize attention.

- Asia Pacific markets have shown more resilience than Europe and the Americas, suggesting that capital is already comfortable pivoting toward “newer” real estate geographies.

- The re pricing is still incomplete in some core markets, making relatively high growth markets with clear legal regimes more attractive on a risk adjusted basis.

Saudi’s policy bet is that by clarifying where and how foreigners can own real estate, and by aligning procedures with international practice, it can capture a larger share of this selective capital at the exact moment global portfolios are being re-balanced.

Regional Context: GCC Real Estate Moving from Construction to Capital Markets Logic

Across the GCC, real estate has already become a central channel for diversification capital. One estimate from CBRE suggested that, even by 2022 2023, Saudi Arabia alone accounted for nearly two thirds of total announced real estate and infrastructure investment in the region. Dubai’s experience shows what happens when foreign ownership, capital markets depth, and tourism scale align: foreign investors have driven a substantial share of residential stock ownership, and transaction data now supports detailed analysis of international flows by nationality and asset type.

For Saudi investors, the opening of domestic markets to foreign ownership therefore has a dual meaning.

- Outbound, Saudi capital has already been buying in global markets with strong freehold regimes.

- Inbound, the Kingdom is shifting from a primarily domestically owned stock toward a mixed structure where global institutions, regional family offices, and high net worth individuals may join locals on the cap table.

In that sense, foreign ownership reform is not merely a legal update; it is an invitation to treat Saudi real estate as a global asset class with transparent pricing, repeatable exit routes, and cross border comparability.

Saudi Market Baseline: Prices, Volumes, and Regional Imbalances

Before foreign buyers arrive in size, it is critical to understand the domestic starting point.

Volumes and activity. As noted, 2024 real estate transactions reached about SAR 2.5 trillion, covering more than 622,000 deals and roughly 5.8 billion square meters of land and built up area, according to Ministry of Justice data. A digital “Real Estate Market” platform now captures more than 210,000 transactions in a half year, with granular data on value, location, area and price per square meter.

Riyad Capital’s Q2 2024 Saudi Economic Chartbook illustrates how transactional activity is distributed: Q1 2024 real estate transactions rebounded 70% year on year, with more than 50% of value in Riyadh region, 29% in Makkah, 12% in Eastern Province and the remainder elsewhere.

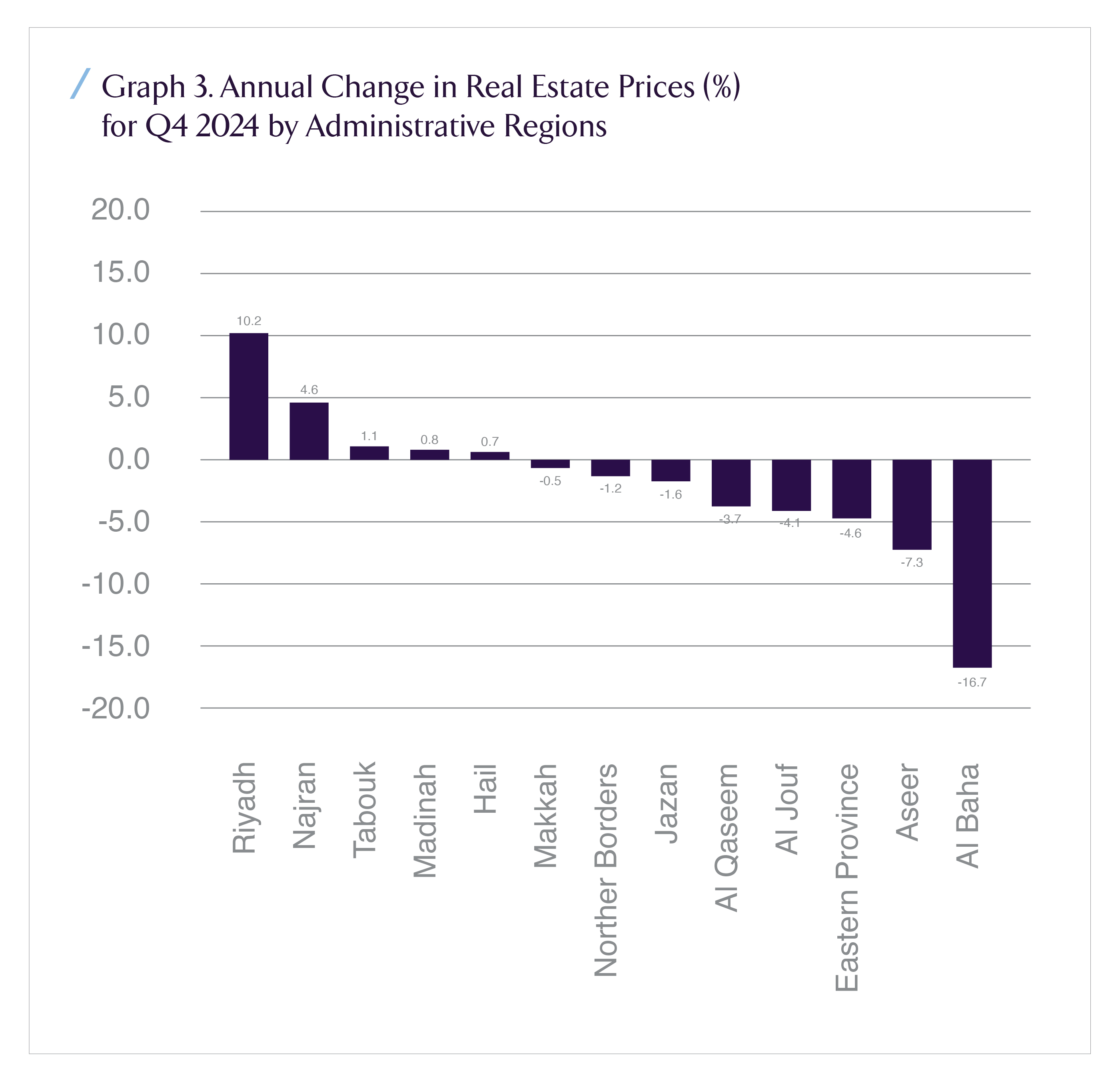

Prices and regional differentiation. On the price side, the General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT) has recently modernized the Real Estate Price Index (REPI), resetting the base year to 2023 and incorporating geospatial AI to classify transactions. The latest Q4 2024 release shows:

- The overall index was up 3.6% year on year, with residential prices up 3.1%, commercial up 5.0%, and agricultural up 2.8%.

- Riyadh recorded a 10.2% annual price increase, while Makkah and the Eastern Province saw declines of 0.5% and 4.6% respectively.

This chart matters for foreign ownership analysis because it visually separates regions where prices are still compounding (Riyadh, Najran, Tabuk) from those where they are already correcting (Al Baha, Asir, Makkah, Eastern Province). For allocators, the foreign ownership regime will not land on a flat surface; it will interact with pre-existing regional momentum, local supply pipelines, and policy shocks such as Riyadh’s five year rent freeze.

The New Law: From Prohibition to Calibrated Access

Under the previous framework (the 2000 law and its implementing regulations), foreign individuals and companies could generally own property in much of the Kingdom, but with critical exclusions and procedural frictions notably broad prohibitions on non Saudi ownership in Makkah and Madinah except by inheritance, and a heavy reliance on case by case licensing for large, non residential projects.

The new Law of Real Estate Ownership by Non Saudis, published in the Official Gazette on 25 July 2025, reshapes this in several ways:

- It unifies and updates the rules governing ownership and use rights (including usufruct and long leases) by non Saudis, replacing the older law.

- It grants foreign individuals and legal entities the right to own most types of real estate across the Kingdom, with restrictions delegated to secondary regulation (notably by the Real Estate General Authority - REGA).

- It introduces a structured framework for ownership in Makkah and Madinah via designated zones and specific conditions, including religious status requirements and approvals for certain categories of investors.

- It clarifies that foreign state entities and international organizations can own real estate for diplomatic and related purposes under reciprocity principles.

Secondary sources and REGA’s own FAQ emphasize that, while access is broader, it is not unlimited: specific geographic polygons in Makkah and Madinah will be designated for eligible non Saudi owners (primarily Muslim individuals and Saudi companies with foreign shareholders), while other areas remain restricted.

At the same time, officials have signaled that new fees and taxes will apply to foreign property ownership from 2026, including a 10% levy on non-resident foreign owners as part of a package aimed at managing speculation and ensuring some fiscal capture of foreign inflows.

For investors, the key takeaway is not simply “foreigners can now buy more.” It is that Saudi is moving toward a modern, codified regime that:

- distinguishes between different types of foreign capital (individual, corporate, state, and fund);

- uses zoning and fee structures to manage externalities in sensitive areas; and

- embeds the regime within a broader, digital data environment (REPI, MoJ Real Estate Market platform, REGA licensing portals).

What Changes for the Market: Pricing, Liquidity, and Segment Dynamics

1. Pricing Power in Gateway Micro Markets

In global experience, opening freehold markets to foreign capital tends to have its sharpest effects in a few segments:

- central business districts with limited new land supply;

- tourism and second home corridors;

- religious or heritage sites with global appeal.

For Saudi, that suggests:

- prime Riyadh districts already under pressure from corporate relocation and mega project spillovers;

- coastal corridors such as Jeddah and the Red Sea region;

- designated zones in Makkah and Madinah serving religious tourism, where supply is structurally constrained and demand is globally diversified.

Foreign participation will not automatically drive prices higher across the board. The Q4 2024 REPI data show that even within the same national market, regions can diverge sharply. The effect instead will likely be to:

- raise clearing prices in specific micro markets where foreign and domestic demand stack on top of each other;

- increase dispersion between assets with institutional grade documentation and governance and those without;

- compress cap rates on assets that can be easily underwritten by international credit committees (standardized leases, Ejar compliance, transparent service charge regimes).

2. Liquidity and Exit Optionality

The more reliable the foreign ownership framework, the more plausible it becomes to treat Saudi assets as part of a global core plus or value add mandate. That, in turn, changes exit logic:

- For domestic developers, a future buyer could be a foreign REIT, a regional sovereign fund, or a cross border private vehicle, not only a local family office.

- For Saudi institutional investors, co-investment structures with foreign LPs become easier to design because both sides can appear on title in a predictable way.

Combined with transaction level data from MoJ’s Real Estate Market platform, this should gradually thicken the order book and improve price discovery particularly in segments where today much of the trading is bilateral and relationship driven.

3. Religious Tourism and Hospitality Corridors

The most politically sensitive (and commercially meaningful) component of the reform is the pathway into holy city real estate. Even with tight zoning and eligibility criteria, enabling foreign participation in parts of Makkah and Madinah creates a new investable universe tied to Hajj and Umrah flows, religious conferences, and year round pilgrimage related tourism.

This will likely:

- increase institutional interest in hospitality and serviced residential formats with high occupancy volatility but structurally deep demand;

- favour operators able to manage yield across peak and off peak seasons while complying with religious and regulatory constraints;

- raise the bar on asset level ESG and crowd management standards, as international capital brings its own frameworks and reporting requirements.

Challenges: Policy, Market, and Execution Risks

The opportunity set is substantial, but so are the frictions. Key challenges include:

Regulatory clarity and stability. Until implementing regulations, zoning maps, and fee schedules are fully published and tested in practice, there is a non-trivial “policy execution risk” discount. For global investors, the question is not just “what is allowed?” but “how often might it change, and how will disputes be resolved?”

Data depth at asset level. National indices such as REPI and aggregate transaction statistics are improving rapidly, especially with the adoption of geospatial AI for price measurement. But institutional investors will demand asset level audit trails: historical occupancy, rent rolls, arrears, maintenance histories, and ESG metrics. Many existing assets will require significant data “clean up” before they are investable.

Interaction with other policies. The new regime does not exist in isolation. Investors must factor in:

- rent freezes (e.g., Riyadh’s five year freeze) that cap near term income growth while supply rebalances.

- White Land Tax expansion and enforcement, which affects land banking economics and may accelerate the release of plots in high value corridors.

- sector specific regulations (tourism, hospitality, healthcare, education) that affect permitted uses and licensing timelines.

Capital structure complexity. As foreign and domestic capital blend, capital stacks will become more complex: senior bank debt, Islamic project finance, mezzanine tranches, and equity from multiple jurisdictions, each with different tax and regulatory profiles. Structuring these stacks to withstand rate volatility and refinancing “walls” will be non trivial, mirroring the challenges highlighted in global markets.

Strategic Responses and Structures: How Investors Can Position

Given the above, sophisticated Saudi and international investors are likely to respond in several ways.

First, expect a pivot toward thematic vehicles rather than broad, undifferentiated exposure. For example:

- a holy cities hospitality and serviced residential fund, restricted to designated zones and calibrated to pilgrimage calendars;

- a Riyadh centric mixed use vehicle that combines rent regulated residential with market rate office and retail, smoothing income through policy cycles;

- a logistics and warehousing platform targeting corridors aligned with NEOM, the Red Sea, and other mega projects, where foreign ownership rights could support regional distribution networks.

Second, expect more partnership driven structures:

- joint ventures where Saudi developers contribute local execution capability and land, while foreign partners bring capital and operational platforms;

- club deals between Saudi institutions and foreign pension funds or insurers, with co governed investment committees and risk frameworks.

Third, anticipate a premium on regulatory grade governance. Assets that can demonstrate:

- full Ejar registration of leases;

- clear segregation of owner and association responsibilities in strata or community schemes;

- audited service charge accounts and sinking fund policies;

- environmental and health and safety compliance aligned with international reporting standards,

will command better pricing not only because they reduce risk, but because they are legible to global investment and credit committees.

Benefits: Why This Matters for Saudi Allocators Specifically

For Saudi investors, the foreign ownership regime is not simply about selling to outsiders. Done well, it can improve the risk return profile of domestic allocations.

- Liquidity and valuation discipline. A more diverse buyer universe, including foreign institutions, can deepen secondary markets, tighten bid/ask spreads, and provide more reliable mark to market signals.

- Portfolio diversification within the Kingdom. With foreign buyers potentially more concentrated in certain segments (e.g., high end hospitality, branded residences, religious tourism zones), Saudi investors can allocate opportunistically into segments that remain dominated by local demand, capturing different beta and idiosyncratic risk profiles.

- Knowledge transfer. Co investment with experienced global operators can accelerate adoption of best practices in asset management, ESG reporting, digital tenant engagement, and data driven pricing.

- Fiscal and macro stability. If fee and tax regimes are calibrated correctly, foreign property ownership can generate non-oil fiscal revenues and support balance of payments resilience without undermining housing affordability objectives.

For global investors, the benefits are complementary: exposure to an economy with strong sovereign balance sheet metrics, high population growth in key cities, structural tourism drivers, and a multi decade pipeline of public backed urban and infrastructure projects.

Recap: From Legal Text to Allocation Thesis

Saudi Arabia’s new foreign ownership regime, due to take effect around January 2026, is best understood as an enabling layer in a larger transition: from a real estate market driven primarily by domestic buyers and state linked development, to one where local and global capital operate within a common, codified framework.

Global capital flows into real estate are currently subdued, but history suggests that regime clarity and macro stability attract disproportionate interest once the cycle turns. The PwC / MSCI data on post 2012 capital flow recoveries, coupled with emerging GCC transaction and price index data, provides a useful analogue and the charts highlighted in this article give a concrete starting point.

Domestically, REPI’s new methodology, MoJ’s transaction platforms, rent freeze directives, and land use policies together form the operational environment into which foreign buyers will step. The opportunity lies not in extrapolating a simple “foreigners will push prices up” narrative, but in building nuanced, region and segment specific allocation theses that:

- respect zoning and policy constraints, especially in holy cities;

- exploit improved data and digital infrastructure for underwriting;

- use partnership structures to share execution risk; and

- align investment horizons with the long cycle nature of Vision 2030 urban and infrastructure projects.

For Saudi allocators, the strategic question is straightforward: when global buyers arrive with durable mandates, will you meet them as sellers, partners, or co owners? The answer will determine not just deal level returns, but how Saudi portfolios participate in and shape the next phase of global real estate capital flows.