Overview: A Bilateral Framework for Hard Power AI

The Saudi/US Strategic Artificial Intelligence Partnership, signed in Washington on 19 November 2025, is not another MOI about “innovation” in the abstract. It is a government to government framework that explicitly links advanced semiconductors, AI infrastructure, cloud services, and high value technology investments to long term economic security.

For Saudi investors, the signal is clear: the kingdom is moving from a “buyer of capacity” model towards being a co architect of sovereign compute and standards underpinned by US aligned export rules and safety regimes, rather than workarounds on the margin of controls. At the same time, the deal coincides with authorisations for US companies to export advanced AI chips to Saudi entities like Humain, and with multi billion dollar commitments to build 500 1,000 MW scale AI data centres in the kingdom.

The partnership therefore needs to be read not as a headline, but as an operating environment: one that will shape where racks are sited, which models can be trained under which legal regimes, and how talent and standards are embedded into the ecosystem. This article frames those dynamics in three planes: sovereign compute, standards, and talent and their practical consequences for Saudi capital allocation.

Global Landscape: AI as an Energy and Standards Constrained System

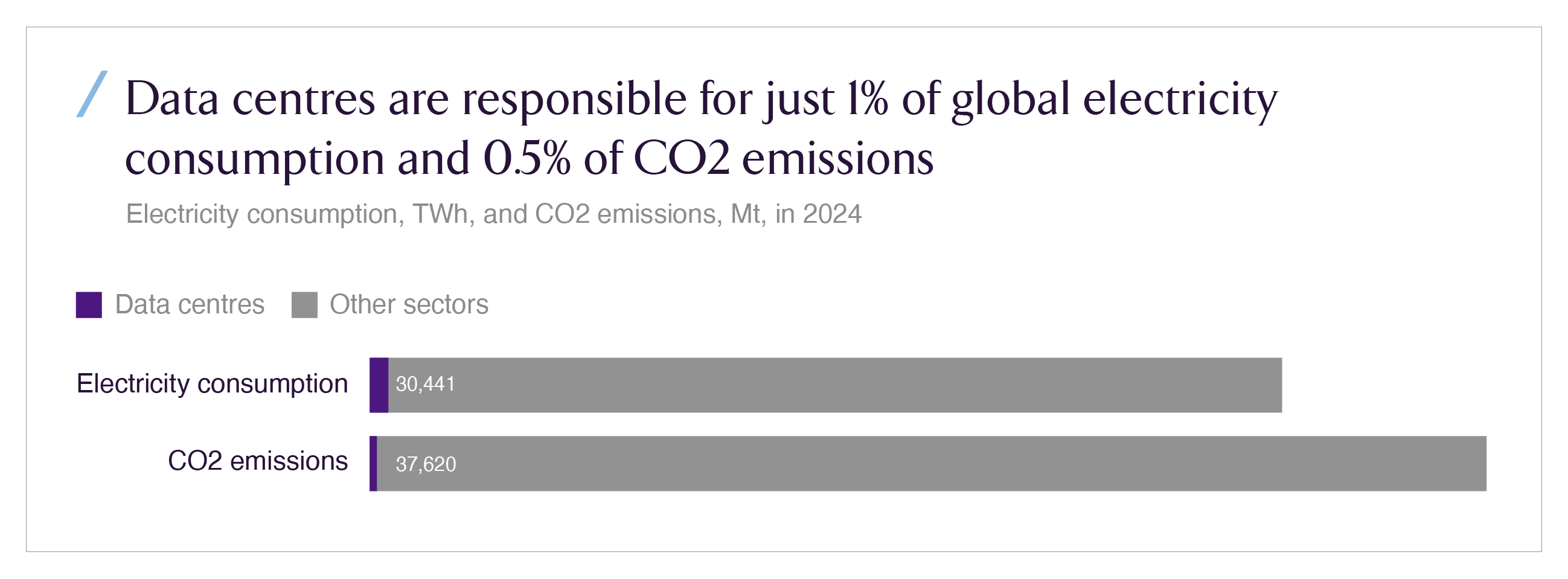

The starting point is physical. AI is now firmly compute and power constrained. The International Energy Agency’s 2025 work on “Energy and AI” and related analysis shows data centres already account for a little over 1% of global electricity demand and around 0.5% of CO₂ emissions, with AI the single most important driver of growth.

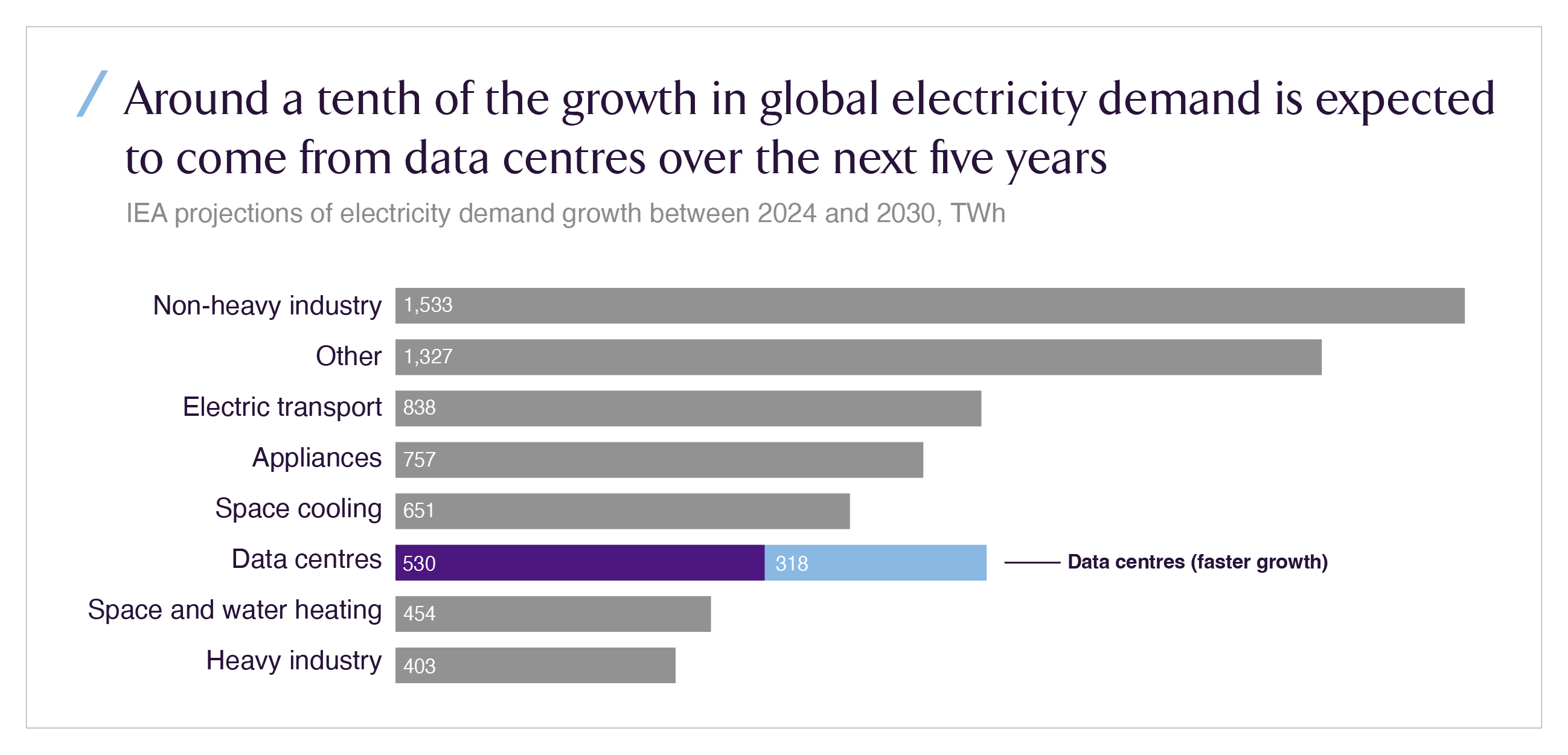

Under the IEA’s central case, global data centre electricity use more than doubles between 2024 and 2030, adding roughly 530 TWh of demand equivalent to today’s electricity consumption of Japan of which AI drives a rising share.Even in that scenario, data centres are responsible for around 8 12% of net demand growth, depending on deployment speed. This is enough to stress grids in key hubs (US, EU, parts of Asia), but not yet enough to dominate the global load curve.

This physical intensity interacts with two other global constraints:

- Semiconductor supply and export controls. Advanced GPUs and accelerators remain highly concentrated in a small number of US and allied vendors, subject to evolving export regimes that explicitly reference “advanced computing items” and AI related national security risks.

- Fragmenting standards and safety frameworks. The US, EU, UK and China are each moving towards their own AI safety baselines, model classification schemes, and disclosure requirements. For cross border AI companies, this creates a patchwork of overlapping obligations around model risk, transparency, and compute thresholds.

In that context, the Saudi US partnership is less about symbolism and more about choosing a primary standards and supply chain stack. It anchors Saudi Arabia’s AI scale up to US aligned hardware, safety norms, and cloud architectures, while also giving US policymakers a structured way to treat Saudi AI expansion as “inside the tent” rather than as a leakage channel.

Regional Landscape: Gulf Competition on Chips, Clouds, and Hubs

Across the GCC, AI has shifted from a policy aspiration to a capital programme. Multiple states have announced sovereign AI companies, GPU procurements, and national data centre roadmaps, each seeking to become the region’s compute and model hub.

Saudi Arabia’s trajectory is particularly aggressive. In 2024, the kingdom signalled plans for a roughly USD 40 billion AI investment fund spanning semiconductors, data centres, and AI companies. In 2025, PIF backed Humain emerged as the primary vehicle for national AI infrastructure aligned with wider initiatives such as Alat on advanced electronics and the National Data Centre Strategy.

Parallel activity is visible in the UAE, which is building its own hyperscale AI complexes (for example the “Stargate” initiative backed by G42 and US vendors) and competing for model training mandates in multiple languages and domains.

From an investor’s perspective, this regional landscape has three practical implications:

- Asset density is rising in just a few nodes. A limited set of urban clusters Riyadh, NEOM’s industrial zones, Abu Dhabi, Dubai are capturing the bulk of new AI data centre MWs and chip allocations.

- Partnership alignment matters. Deals that sit comfortably within US export regimes and safety frameworks are attracting more patient US capital and technology partners.

- AI infra is being financialised. GPU pools, availability zone footprints, and long term power contracts are becoming investable instruments in their own right, with returns dependent on utilisation ratios, model mix, and regulatory stability.

The Saudi US AI partnership therefore re-positions Saudi Arabia not just as a regional competitor, but as a preferred US aligned hub for AI workloads serving Arabic, Islamic finance, energy, logistics, and defence adjacent use cases.

Saudi Landscape: From Vision to Hardware and Governance

Prior to the November 2025 agreement, Saudi Arabia had already moved from strategy to execution on AI:

- SDAIA’s national AI strategy embedded AI as a core Vision 2030 lever, including data governance frameworks and the NDMO regime.

- The kingdom established a series of data centres and cloud regions in partnership with hyperscalers and regional providers.

- AI talent programmes expanded, with thousands of students and professionals moving through local and international AI training tracks.

Crucially, 2025 data from Stanford’s AI Index showed Saudi Arabia ranked third globally on two fast moving metrics: the share of “leading AI models” linked to Saudi based organisations, and the growth rate of AI related jobs (28.7% year on year).This is not yet a measure of depth comparable to the US or China, but it is a sign that Saudi institutions and firms are already operating close to the frontier in specific niches, particularly Arabic language models and domain specific AI for energy, logistics, and finance.

At the same time, Saudi investors faced three structural constraints:

- Hardware risk. Access to the latest US accelerators was constrained by export rules, leaving investors uncertain about the long term viability of large scale GPU projects that depended on waivers or indirect supply routes.

- Policy arbitrage risk. Without an explicit bilateral framework, any divergence between US and Saudi AI safety or data protection rules could have reduced the portability of models and data across jurisdictions.

- Talent bottlenecks. While AI job growth was strong, the local pool of experienced AI engineers, ML Ops specialists, and AI literate regulators remained thin relative to announced capital.

The new strategic partnership is designed to address these gaps: it explicitly wraps semiconductors, cloud and AI infrastructure, application development, national capability building, and high value investment under a single political and policy umbrella.

Sovereign Compute: Chips, Data Centres, and Power as an Asset Class

The most tangible near term dimension of the partnership is sovereign compute: how many chips, in which racks, under which legal and security conditions.

Public reporting around the partnership and parallel deals indicates:

- US authorities have now authorised exports of advanced AI chips (Nvidia Blackwell class and equivalents) to Humain, with quotas on the order of tens of thousands of units initially and a roadmap towards hundreds of thousands.

- Humain, Nvidia, AMD, xAI and other vendors are aligning around multi hundred megawatt data centres in Saudi Arabia, with target capacity of up to 1 GW of AI infrastructure by 2030.

In energy terms, each 500 MW class AI data centre campus is equivalent to a mid size industrial city. Against that backdrop, the global picture from Carbon Brief and the IEA is instructive: data centre electricity demand is projected to more than double by 2030, reaching ~945 TWh in the central case, with AI responsible for a rising share.

For Saudi investors, this places AI data centres firmly in the category of infrastructure plus: assets that combine:

- Long dated power purchase and grid connection agreements

- Globally constrained hardware (GPUs, networking)

- Sticky, high margin customers (cloud providers, sovereign entities, global AI labs)

The partnership with the US, by clarifying export and security expectations, de risks the hardware leg of that stack. It does not eliminate all risk export regimes can tighten but it converts “grey zone” dependence into a negotiated, monitored, and therefore plannable framework.

Standards and Safety: Aligning with US Centred Governance

The second layer of the partnership is standards and safety. While the formal joint statement language is diplomatic, the surrounding policy context is clear: both sides are committing to “safe, secure, and trustworthy AI,” to shared principles on risk based regulation, and to cooperation in international fora shaping AI norms.

For Saudi Arabia, this has several concrete implications:

- Regulatory design. Domestic AI laws and guidelines (for example, those emerging from SDAIA, NDMO and other bodies) are likely to converge with US aligned concepts: model classification tiers, obligations scaling with capability, and emphasis on safety testing, monitoring, and incident reporting for high risk models.

- Assurance tooling. US partners bring not only hardware but also model evaluation frameworks, red teaming practices, audit tools, and governance platforms. These can be localised to Saudi regulatory and cultural context but will still reflect the underlying US R&D ecosystem.

- Cross border interoperability. Models and AI services deployed from Saudi based data centres into US adjacent markets (for example, via US cloud providers) will be easier to certify if the underlying standards and documentation are aligned.

For investors in AI infra, platforms, and applications, this means that governance itself becomes investable. Demand will rise for companies that operationalise compliance continuous model monitoring, audit ready logs, and sector specific assurance (health, finance, critical infrastructure) as an integrated part of the tech stack. Those firms are likely to enjoy both domestic demand and export potential, given their compatibility with US and allied regimes.

Talent and Workforce: Making the Partnership More Than Hardware

The third pillar is talent. AI is already tightening global labour markets for specialised skills; the US Saudi partnership signals an intent to accelerate joint workforce development rather than simply importing expertise.

Two data points matter here:

- Stanford’s AI Index linked analysis shows Saudi Arabia ranking third globally in growth of AI related jobs (28.7% annual growth) and among the top countries in contribution to “leading AI models,” indicating that a meaningful part of the local labour market is already engaged in frontier work.

- A 2025 e& / IBM study across the MENA region finds that 65% of CEOs are pushing their organisations to embrace generative AI above the global average with 54% viewing advanced gen AI as critical for competitive advantage.

Taken together, these signals show demand for AI talent in Saudi Arabia is not hypothetical: boards and executives are already committing to programmes that embed AI into operations and decision making.

Within the partnership, talent related mechanisms are likely to include:

- Joint research centres linking Saudi universities and US institutions

- Scholarship and exchange programmes in AI and semiconductor design

- Co developed training curricula for regulators, auditors, and sectoral specialists

For investors, this shifts the opportunity from simply backing “AI companies” to backing the talent supply chain: specialised training providers, AI native enterprise software vendors serving Saudi corporates, and platforms that lower the barrier to deploying compliant AI workflows inside existing organisations.

Value Creation Opportunities and the Friction Points

The partnership creates a fertile environment, but it does not remove friction. Key challenges include:

- Export control volatility. Even with a framework agreement, US export policy on advanced chips can tighten if geopolitical conditions change. Investors in large GPU pools must therefore model scenarios in which renewal licences become more restrictive or impose stricter monitoring, adding operational overhead or limiting resale.

- Concentration risk. Tying national AI capacity to a narrow set of US hardware and cloud vendors creates vendor concentration risk. This is particularly acute for long life assets such as data centres, where stranded hardware or proprietary networking can limit future optionality.

- Grid, water, and land constraints. AI campuses require high quality grid interconnections, cooling water (or dry cooling alternatives), and land close enough to fibre routes but far enough from urban constraints. Saudi has more flexibility than many countries, but siting decisions will still require grid co planning and, in some regions, desalination linked water allocations.

- Talent absorption. Rapid ramp up of AI jobs can outpace the capacity of organisations to productively absorb new talent, leading to under utilised specialists or fragmented internal AI projects.

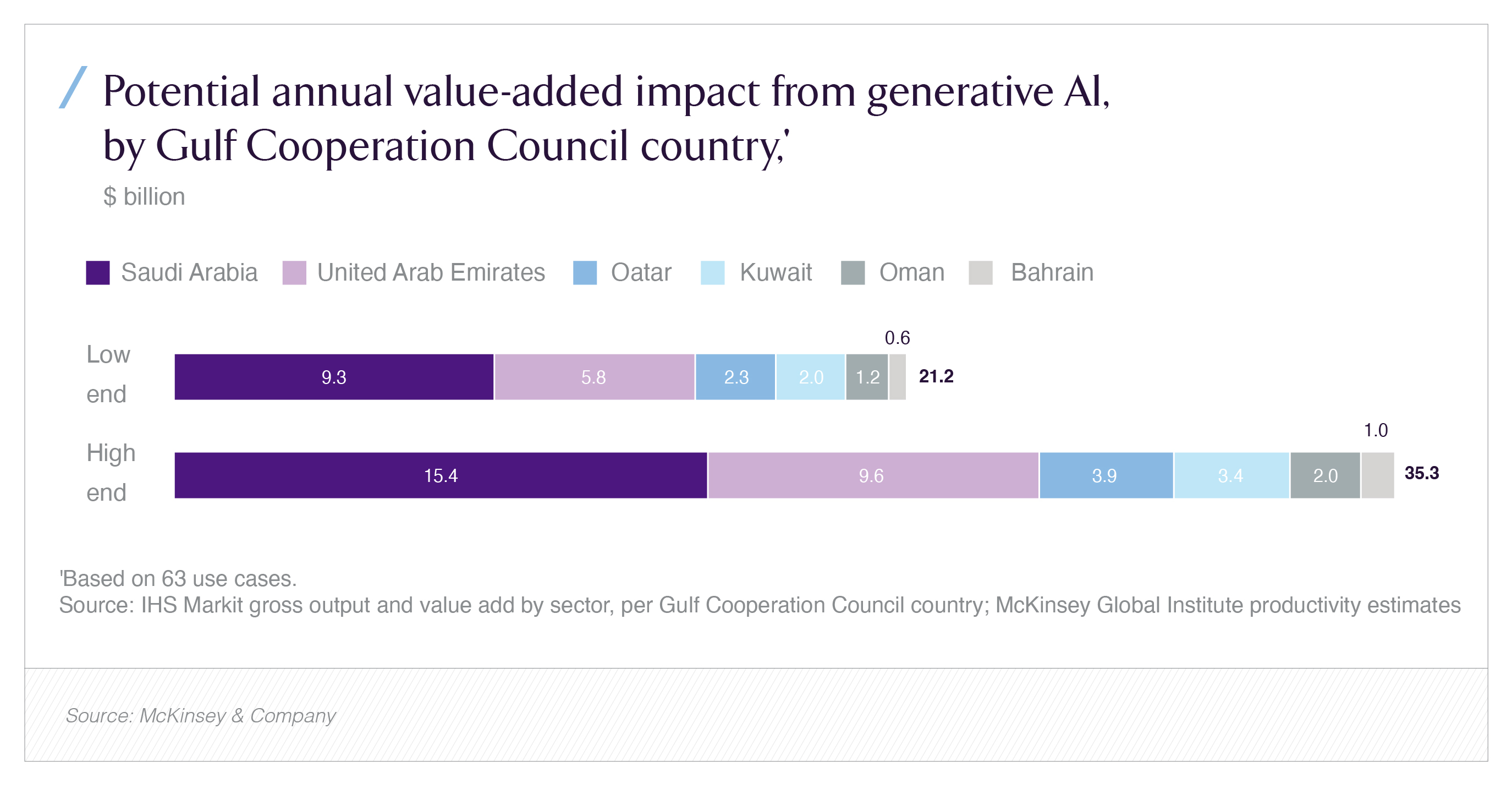

At the same time, the value creation upside is material. McKinsey’s 2024 report card on generative AI in GCC countries estimates that gen AI could add a substantial percentage of GDP equivalent in incremental annual value across sectors such as financial services, energy, retail and public services by 2030 if adoption is scaled.

For Saudi investors, the partnership improves the probability that the kingdom captures a disproportionate share of that value by anchoring the key limiting inputs (chips, standards, and talent pipelines) in a stable bilateral architecture.

Practical Strategies for Saudi Investors

Against this backdrop, Saudi institutional and private investors can translate the partnership into concrete positioning across three layers:

- Infra and hardware adjacent plays.

- Equity or structured exposure to data centre developers, grid connection projects, and specialised cooling or power management solutions tied to AI campuses.

- Participation in GPU and accelerator leasing vehicles that arbitrage utilisation across sectors under compliant export and usage regimes.

- Equity or structured exposure to data centre developers, grid connection projects, and specialised cooling or power management solutions tied to AI campuses.

- Platforms and middleware.

- Backing companies that provide orchestration, observability, safety tooling, and compliance services for AI workflows, especially in regulated verticals (finance, health, critical infrastructure).

- Investing in platforms that localise and govern US origin foundation models for Arabic and Islamic finance contexts while maintaining cross border compatibility.

- Backing companies that provide orchestration, observability, safety tooling, and compliance services for AI workflows, especially in regulated verticals (finance, health, critical infrastructure).

- Talent, services and “AI native” operating models.

- Supporting education and re-skilling ventures that are tightly coupled to Saudi corporate demand and to the standards emerging from the partnership.

- Equity in firms that embed AI into core operations of Saudi based enterprises where alpha comes from process redesign and governance, not just from API access to models.

- Supporting education and re-skilling ventures that are tightly coupled to Saudi corporate demand and to the standards emerging from the partnership.

In each case, the partnership changes the risk/reward profile. Access to US hardware and a clearer safety standards trajectory allow investors to underwrite larger, longer dated commitments, as long as they treat export control and standards evolution as an active risk to be managed, not a solved problem.

Recap: Beyond Optics, Towards Operating Discipline

The Saudi/US Strategic AI Partnership is not a discrete event; it is the governance wrapper around an emerging AI industrial base that includes tens of billions of dollars in semiconductors, 500 1,000 MW class data centres, and a rapidly scaling AI workforce. It positions Saudi Arabia as a US aligned sovereign compute hub in a world where compute is scarce, grid capacity is valuable, and safety standards are still being negotiated.

For Saudi investors, the key is to read the partnership in operating terms:

- On sovereign compute, it de-risks access to advanced US chips and cloud architectures, turning AI data centres into a more bankable infrastructure category provided investors remain alert to export control shifts.

- On standards, it nudges Saudi AI regulation and governance towards US compatible frameworks, expanding the addressable market for Saudi based AI services and creating investable demand for compliance by design tooling.

- On talent, it anchors joint programmes and reinforces a labour market trend already visible in the data: Saudi linked organisations are becoming meaningful contributors to global AI models and job growth.

The next five years will determine whether this partnership crystallises into a durable competitive edge or remains primarily symbolic. For capital allocators in the kingdom, the opportunity is to back assets, platforms, and talent engines that are explicitly designed for this new regime where chips, standards, and people are treated as a single, integrated investment thesis.